Drug development in children can be daunting. There are four key considerations: Safety, Pharmacokinetics (PK), Pharmacodynamics (PD) and the indication.

Safety: In adults, adverse events (AEs) may be related to exposure (drug dependent) or due to the susceptibility of the individual, independent of exposure (also referred to as idiosyncratic, drug independent, pharmacogenomics related, etc). In the vulnerable pediatric population, the AEs seen in adults may occur (albeit with age specific verbatim terms) at the same exposure as adults, but there may be AEs (not seen in adults) related to the susceptibility of this population (at exposures less than that in adults). These susceptibilities exist across the population and are applicable irrespective of drug (PK), its primary or secondary target (PD) and indication (disease). No amount of adult safety data can predict AEs related to the susceptibility in this vulnerable population. The only way these AEs can be identified is by clinical trials in the population. Before advancing trials into this population, it is, however, useful to understand these general susceptibilities. It is convenient to review susceptibilities to toxicity separately for two different age groups – children less than two years and those greater than two – reviewed in other blogs

Pharmacokinetics: This is the subject matter of another blog on Pediatric PK, which is summarized here. As pediatricians, we see three important considerations that impact pediatric PK. These relate to the size of the child, the maturation of the organ and the impact of any comorbidity on organ function. To account for the smaller size (less weight) in children, a non-linear model (allometric scaling) has been found to be more appropriate. This is expressed as

where y is the dependent variable, x the independent variable, a the allometric coefficient and b the allometric exponent. For PK parameters (e.g. clearance) b = ¾

The allometric scaling, however, does not account for immaturity of the organ. This is because while children are small adults, neonates and infants are immature children! The more rigorous method for dosing in neonates and infants is to consider maturation.

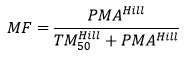

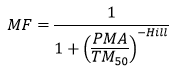

The Hill model for pharmacology has been used to describe maturation:

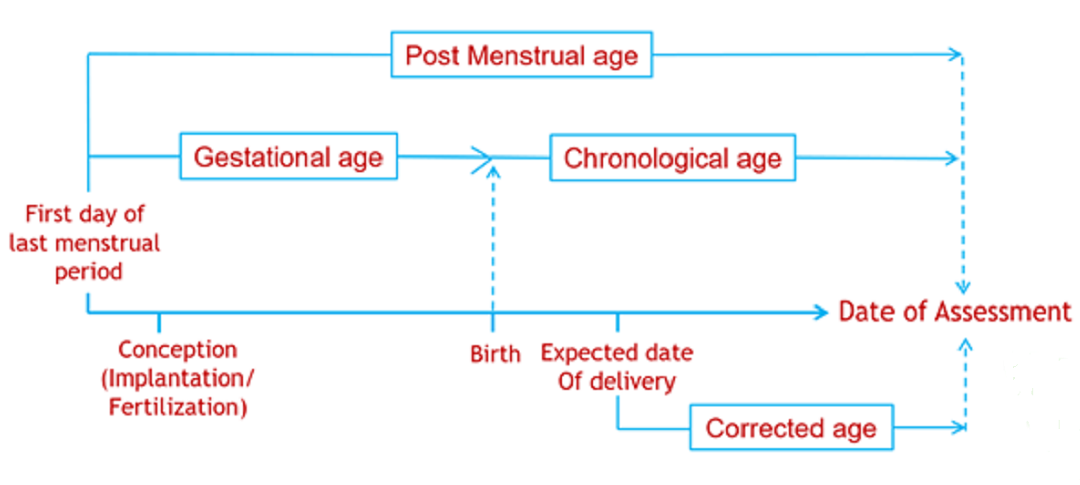

Where TM50 is the maturation half time, and Hill coefficient related to slope of the maturation profile. The Post Menstrual Age (PMA) is used instead of the Post Natal Age (PNA), as maturation can start before birth (e.g. maturation of drug renal clearance begins before birth).

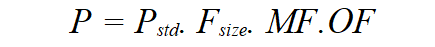

Once size and immaturity are accounted for, one might still need to account for the impact of any limitation in organ function. PK parameters (P) can be described in an individual as the product of size, maturation and organ function influences, where Pstd is the value in a standard size adult size without pathological changes in organ function.

Pharmacodynamics: Developmental PD aspects may impact PK PD relationships affecting potency, efficacy or both. The sigmoid Emax (Hill) model of exposure response in children may be the same as in adults, show reduced potency (shift to right), increased potency (shift to left), reduced efficacy (decreased Emax) or increased efficacy (increased Emax) in children. More details on exposure response (ER) are presented in blogs on Optimizing Extrapolation in Pediatric Programs and Developmental PD

Indication: There are several disease-specific issues that manifest differently in neonates and infants when compared to the older population. These are indication-specific and generalities are not possible.

An understanding of the theoretical considerations for safety, PK, PD and the indication can make drug development in this population so much less daunting. We are happy to say that we have applied these considerations for several drug development programs involving children: Systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, Netherton syndrome, etc.

For more blogs, please visit: https://www.rxmd.com/insights